Introduction

Patients’ transfer from the hospital to primary care during discharge is a risky process, which can result in adverse effects and readmission of the patient. The transfer process and care are not standardized, fragmented and risky. The Root Cause Analysis (retrospective approach to error analysis) enables us to investigate errors that result in adverse events during patients discharging to enhance patients’ safety.

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) is a popular tool for enhancing the safety of patients. However, some studies indicate that RCA lacks enough supporting evidence. Wu, Lipshutz, and Pronovost note that few data support the effectiveness of RCA (Wu, Lipshutz and Pronovost, 2008). They note that the problem lies in the interpretation of RCA. This is because RCA has no set standards that hospitals can rely on in interpreting data. As a result, this problem reduces the utilization of RCA as a tool for enhancing patient safety. In addition, RCA results cannot work across multiple institutions. This is because RCA mainly focuses on a specific error. However, the use of RCA has increased in analyses of sentinel events and serious events (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 2005).

According to Hebrew Senior Life Institute for Aging Research, “rehospitalization of senior patients within 30 days of discharge from a skilled nursing facility (SNF) has risen dramatically in recent years, at an estimated annual cost of more than $17 billion” (Hebrew Senior Life Institute for Aging Research, 2011). However, a recent study has indicated an improvement in discharge disposition after intervention measures that focused on “standardized admission templates, palliative care consultations, and root-cause-analysis conferences” (Randi et al, 2011). Randi and colleagues noted that the rate of patient rehospitalization reduced from “16.5 % to 13.3% while discharge to homes increased from 68.6% to 73.0% and discharge to long-term care dropped to 11.5% from 13.8%” (Randi et al, 2011).

Importance of the study

According to Randi and colleagues, the rate of rehospitalization within 30 days affects at least one out of five Medicare beneficiaries. This results in an estimated cost of $ 17.4 billion. At the same time, patients of SNF experience high rates of early and unplanned rehospitalization (Randi et al, 2011). This results in risk factors such as acute medical conditions, certain diagnoses, and depression among others to the patient. Still, readmission can result in dependence that leads to disability among senior patients. This implies that such readmitted patients shall need long-term care facilities.

Following several cases of readmission, the need to reduce readmission has become a matter of national concern. The health care reform law puts it that Medicare shall end all payments of cases that result from preventable rehospitalization from October 2012. These conditions include pneumonia and heart failure. Still, after two years, the program shall include other medical conditions. This is because rehospitalization affects the national health system, particularly from preventable medical conditions.

Therefore, any intervention aims to enhance patient care and safety, and aid nurses recognize that provisions of care and safety are fundamental parts of their duties during the transition of patients.

Problems during and after discharge

The report, To Err Is Human, of the IOM notes that most medical errors occur due to “systemic problems instead of poor performance among individual providers” (Forster, Murff and Peterson, 2003). Systemic problems include hospital discharge. Several conditions exist in the discharge process that causes failures to patients. Nurses normally rely on knowledge, rules, and skills to ensure optimal care for patients. However, the process experiences many opportunities for “lapses, slips, mistakes and risky occurrences” (Forster, Murff and Peterson, 2003).

In this context, nurses must understand causes of errors and intervention measures that can prevent or reduce such errors before they occur and cause harm to patients. RCA should take into account both active and latent errors that occur during the patient discharge process. Active errors mainly occur during decision-making processes when discharging the patient at the care point. Thus, RCA should identify different types of errors that occur during patient discharge at the hospital. At the same time, RCA should also show the relationship between active and latent errors.

System failures or latent conditions can result in errors. Some of these errors may result from organizational processes. For instance, hospitals may allocate the responsibility of discharging patients to nurses and their juniors. However, the nature of “nurses’ works and other areas of interests such as new admissions may render the discharge of a patient a low priority” (Randi et al, 2011). This may result in poor discharge processes.

There are several people such as “nurses, caregivers, trainees, and support staff taking parts in patient discharge” (Randi et al, 2011). This results in a fragmented process for patient discharge with no definite roles for these participants. As a result, there are no proper communications, coordination, gaps, and repetitions.

RCA and reviews of medical documents show consistent results in discharge processes. According to Colorado Foundation for Medical Care (CFMC), patients experience readmissions because of “unmanaged and deteriorating conditions, the use of suboptimal medication regimens, and return to emergency departments instead of accessing other types of medical services” (Colorado Foundation for Medical Care, 2012). We can attribute the cause of discharge problems to three factors based on the system failure. First, there is poor coordination or engagement of the patient and families in the provision of effective care after discharge. Second, there are no standard or agreed processes of patient transfer and management of medical conditions. Finally, there is no effective or reliable information-sharing process among stakeholders.

A number of intervention measures aim to address these gaps. However, these interventions should focus on all stakeholders. Thus, all interventions should aim at providing coordinated relationships among all care providers.

Randi and fellow researchers conducted a research among physicians and patients readmitted within 90 days and noted several factors as major contributors to readmission. There were cases of poor support in terms of social, financial and familial support, premature patient discharge, lack of adherence to the medication recommendations, instructions, and follow-up procedures. Some patients also engaged in substance abuse. Homelessness also contributed to readmission and other factors beyond the patient’s control. Patients who had low levels of self-control in relation to diets and other activities also faced high rates of readmission. Finally, some patients also delayed seeking medical attention resulting in rehospitalization.

Solutions and the role of nurses

RCA analyses have generated some solutions for discharge process and patient safety during transfer to care settings. First, there should be a clear distinction in roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders. This is because a lack of clear delineation in responsibilities leads to confusion and repetition of roles. Second, nurses should engage in patient education during their stay at the hospital. This process should extend beyond the period of discharge. Third, the flow of information should improve between the hospital and primary care providers. Fourth, nurses should enhance the keeping of records and capturing necessary “information of the patient throughout the hospital stay” (Randi et al, 2011). Fifth, discharge should have a written plan. This plan should be comprehensive and address areas of key concerns such as “patient education, follow-up care, therapies, medication, dietary recommendations, changes in lifestyles, and instructions about what to do if the condition worsens” (Randi et al, 2011). Sixth, nurses should ensure that they complete the discharge plan before they discharge the patient. At the same time, nurses should identify patients who may be susceptible to readmission and provide contact details to such patients. Nurses should also ensure that all information regarding the patient discharge should be ready for the primary care provider earlier enough before the discharge day. This aims at eliminating last-minute errors during the discharge process and averting risks. Nurses should give patients their discharge information and explain any issue that may arise due to language barriers, jargon, or different level of education.

Any solution to ensure safe patient transition in the acute care setting should have management and leadership approval. Approval is necessary due to procedural changes from the normal processes. In addition, successful change needs champions to ensure effective implementation. These may include nurses who can promote change by organizing stakeholders’ meetings and incorporating various solutions into discharge practices.

Nurses should also ensure that patients have palliative care after discharge. This implies that nurses must make arrangements for such care. This should have positive outlooks and effects for discharge patients. In case of readmission, nurses should examine factors that caused the rehospitalization of the patient and find solutions. The search for solutions also means teamwork among nurses to find solutions that enhance patients’ safety and care quality during hospital stay and discharge.

We must recognize that such solutions for enhancing safety during discharge should be long-term. Thus, they require sustainability measures. This process should also involve follow-ups with patients. Improving discharge processes should involve collecting information after the discharge in order to enhance the effectiveness of proposed solutions. Any cause of readmission should act as a source of relevant data for evaluating the effectiveness of interventions.

RCA should also involve regular conferences among stakeholders. Such meetings provide opportunities for participants to report challenges, successes, and provide new alternatives. This creates an environment where nurses can recognize their efforts in enhancing patients’ care and safety in hospitals.

Conclusion

RCA should aim at creating programs that can reduce risks during discharge. RCA should also look at “unexpected occurrences and outcomes and identify all underlying causes to formulate solutions that can improve the situation” (Colorado Foundation for Medical Care, 2012). RCA relies on data. Thus, we can create reliable solutions from such data.

RCA recognizes that systems and processes are likely to fail and result in adverse events. As a result, it does not focus on individual performance. Thus, effective RCA analysis should create programs that can enhance discharge processes and improve patient care and safety. However, the lack of enough data and coordination to support RCA should encourage further research to prove its effectiveness. In addition, scholars interested in patient safety during discharge should also apply other techniques to complement RCA to understand complex processes that hinder provisions of quality healthcare and safety to patients.

References

Colorado Foundation for Medical Care. (2012). Root Cause Analysis. Web.

Forster, J., Murff, H. and Peterson, F. (2003). The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med.,138, 161–167.

Hebrew Senior Life Institute for Aging Research. (2011). Reducing avoidable rehospitalizations among seniors: Unique approach improves discharge disposition and patient outcomes. Web.

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. (2005). National patient safety goals. Web.

Randi, B., Richard, N., Ron, R., Margaret, B., Robert, S., Sharon, V., and Michael, P. (2011). Improving Disposition Outcomes for Patients in a Geriatric Skilled Nursing Facility. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 1-5.

Wu, W., Lipshutz, M., and Pronovost, P. (2008). Effectiveness and efficiency of root cause analysis in medicine. JAMA, 299, 685-687.

Appendix

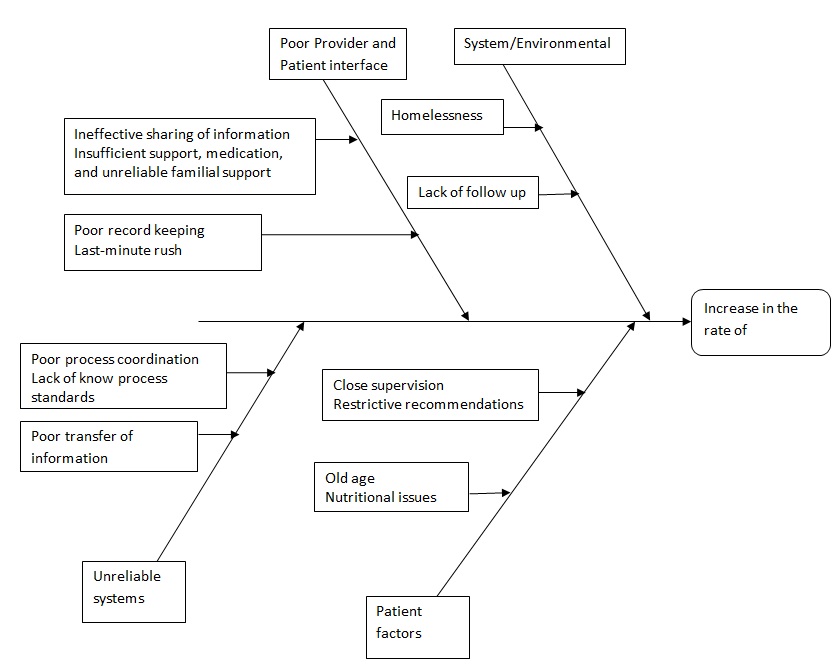

RCA Chart