Introduction

Small and medium enterprises play key roles in many economies throughout the world. They serve personalized needs of clients in different industries (Katua 461-472). SMEs are non-subsidiary business organizations that employ relatively less number of workers, are somewhat independent, and have relatively less output. The number of employees and the level of output differ from countries to countries and from sectors to sectors in defining SMEs.

Mostly, the upper limit of employees that an SME can have is 250, especially in the European countries. Nonetheless, the number is not static as some countries set it as 200 employees. Some countries set the number even higher than 250, like in the case of the US whose upper limits are 500 employees.

Alternatively, the level of assets held by a firm can be used to define an SME. In the EU, for instance, a different method of defining SMEs was initiated in 2005 to give proper guidelines and elaborate framework in matters of legislation. It is worth noting that the region gave more aid to SMEs than large companies and, therefore, distinctive definitions were necessitated. Consequently, the region adopted the new definitions that set the limit to EUR 50 million for medium-size enterprises and EUR 10 million for small enterprises (European Commission 1).

SMEs have relatively similar characteristics (Holátová and Březinová 99-103). First, most of them are somewhat simple. The SMEs simplicity can be linked to the low value of capital needed to start and operate the enterprises, the relatively less stringent legal requirements, and the simple administrative structures. Second, sole proprietors or partners (owners) who are oftentimes extremely ambitious to see the success of their enterprises (in most cases) manage SMEs. Third, the SMEs simplicity allows for relative efficiency when it comes to aspects such as communication, procedures, use of simple production/operation methods, change management, and meeting tailored customer needs (Holátová and Březinová 99-103).

In many economic sectors, it is relatively easy for SMEs to enter and exit a market due to their assets liquidity ratios. It is imperative to note that most of the SMEs assets can easily be liquidated in the short run without incurring significant economic losses. Additionally, exits of SMEs in an economy may have no noteworthy impacts.

Importance of SMEs for developing economies and creating jobs

The role of SMEs in economic development is apparent. They have a unique input in economic development in all the countries and they are a source of employment to more than half of most developing countries’ populations. Additionally, SMEs play a vital role in solving socio economic problems.

The varied definitions given show the emphasis given to the number of employees and, therefore, it is apparent that SMEs are key in the creation of employment. In developing countries, for example, the role creating employment by the SME is extremely evident. In the last decade, for instance, SMEs have been core players in driving the economies of developing countries. Precisely, SMEs account for more than 33% of GDPs of most of the developing countries (The World Bank Group 1). In job creation, SMEs are sources of employment to more than 45% of the workforce (The World Bank Group 1).

A case in point, Algeria is a developing country in Africa that has depended on SMEs for economic sustenance and employment for a considerable time (Alia 160-171). Algeria, like many other developing economies, depends on a minimally diversified economic structure. Therefore, the country faces extremely high financial risk if the strained sources of revenue dwindle.

Algeria is one of the countries that are adversely hit by the falling oil prices. The country also has very high rate of unemployment, especially among the youth. The youth unemployment in the country is approximated to be above 21%. Non-oil sources of revenue are minimal. To mitigate further financial risks, the Algeria policymakers and economists have shifted to the private sector, especially the SMEs due to their pertinence diversifying the economy and their ability to create employment. As such, SMEs have played a key role in the Algeria national economic structure. The SMEs make the biggest percentage of all enterprises. In 2013, for instance, SMEs in Algeria were more than 750,000 firms, comprising more than 90% of the country’s total enterprises (Alia 160-171).

South Africa is another perfect example of a developing economy that has greatly benefited from SMES. In the country, SMEs account for more than 90% of all formal enterprises, contributing more than a third of the country’s GDP. In job creation, SMEs provide approximately 60% of employment (Kongolo 2288-2295).

Decisively, SMEs play vital roles in the economic sustainability and the growth of developing countries. They play significant roles in the transition of economies from depending on simple sources of revenue, like the agriculture-led economies, to more diversified ones. SMEs expand the developing countries’ productive capabilities while adding to the formation of flexible economic systems that allow interlinking of small and mega enterprises.

Definition of SMEs in Saudi Arabia based on different studies

As earlier mentioned, there is no standard globally accepted definition of SMEs. As such, SME definitions are given differently by different economies and different sectors. In Saudi Arabia, a number of studies have given diverse definitions to SMEs. In most cases, the number of employees and the level of outputs play vital roles defining SMEs. The following are some of the many studies that have attempted to define SMEs. However, it is worth noting that a consensus has not been achieved even in a single economy like Saudi Arabia.

In the first study, the author covers official working definitions by the government and private institutions. It is worth noting that the author also studies the SMEs definitions for other 119 economies apart from Saudi Arabia. The study also includes a matrix of variables pertinent to defining of SMEs while giving some of the common characteristics of the SMEs. The author compares three agencies.

First, the author gives the Saudi Arabian General Investment Authority definition of SMEs. The study established that the Saudi Arabian General Investment Authority did not have a recognized legal provision for SMEs definition. Nonetheless, the agency defined SMEs based on the number of employees. For small enterprises, the number of employees should not exceed 60. For medium-size businesses, the agency stipulates that the number of employees should not be more than 100.

Second, the study gives the “Kafala” definition of SMEs. It is worth noting that “Kafala” is a support program for SMEs that work with the Saudi Industrial Development Fund. The” Kafala” defines SMEs as firms whose output is below 20 million Saudi Riyals.

Further, the study gives the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Center at the Eastern Province Chamber of Commerce and Industry definition. The agency provides that small enterprises should have less than 20 employees while the medium enterprises should have 21 to 100 employees (Kushnir 103).

The second study states that SMEs are heterogeneous firms who vary in sizes and nature. Additionally, SMEs operate in diverse markets. According to the study, may players in the Saudi Arabia economy have adopted a given criteria of defining SMEs (Chamber 3-18).

The most adopted definition of SMEs in Saudi Arabia

It is evident that different definitions of SMEs are given in Saudi Arabia. However, it is recommended that the Kingdom should have a clear definition of SMEs.

Status of SMEs in Saudi Arabia

In the gulf region countries (including Saudi Arabia), SMEs have a unique status relative to other parts of the world. As seen earlier, SMEs contribute more than 50 percent of developing countries GDP. It is worth noting that the situation is not different in the developed world. For instance, the OECD countries depend highly on SMEs in running their economy and creating jobs.

Contrary to these scenarios, the Saudi Arabia economy has less dependency on SMEs. SMEs contribution to the Saudi Arabia GDP is approximated to be 33%. Additionally, the number of people employed by SMEs is relatively low. SMEs employ only 25% of the Saudi Arabia workforce, absorbing slightly above 4.5 million employees (Chamber 3-18).

It is imperative to note that substantial numbers of people working for the SMES are expatriates. Saudi nationals make a minimal contribution in providing labor for SMEs, making not more than 10% of the total labor force adopted by SMEs.

SMEs have a stronger footing in Saudi Arabia relative to most of the countries in the gulf region. They are a key strategy in the endeavors to diversify the economy away from hydrocarbons. According to a survey, 1.97 million firms are SMEs making almost 90% of all the business enterprises in the country (Chamber 3-18).

Approximately 85% of the SMEs in Saudi Arabia are owned and managed by sole proprietors. In the Saudi Arabia private sector, SMEs make a vital pillar in the trade arena. Approximately 75% of the SMEs are trade and construction companies while 12% of the SMEs fall under industrial sector.

It is worth noting that the Saudi Arabia government appreciates the vital role SMEs can play in diversifying the economy. Consequently, the government has collaborated with financial institutions to fund SMEs and create programs to enhance entrepreneurial culture. For instance, the government is a key player in mitigating lending risks faced by financiers of SMEs.

In the gulf region, Saudi Arabia is the second country (after the UAE) with the highest number of SMEs. It is commonly agreed that the recent growth of SMEs in the UAE has led to the country’s milestone in diversifying the country’s economy. Compared to the Saudi Arabia GDP contribution of 33%, the UAE SME sector contributes 46% of the country’s GDP. Both the UAE and Saudi Arabia are thriving to achieve further economic diversification by easing the capital funding to promote the growth of their respective SME sectors. The Saudi Arabia Monetary Agency has been very active in protecting the Saudi Arabia market and is likely to take the role of protecting SMEs throughout the gulf region in the future.

Nonetheless, SMEs in Saudi Arabia still face a number of challenges. The most outstanding single challenge facing SMEs in Saudi Arabia is the lack of sufficient funds. More than 90% of the SMEs in the country struggle in funding their ventures. In the country, access to capital is a major challenge that has highly contributed to the shortfall in SMEs’ performance (International Finance Corporation 8). The capital lending to SMEs constitutes approximately 3% of total loans issued in the Saudi Arabia economic sector. The 3% is extremely low relative to the 20% and 25% averages of developing economies and advanced countries respectively (International Finance Corporation 15-19).

Major hurdles in the funding of SMEs in Saudi Arabia

- Unreliability and/or absence of information about most SMEs limit accuracy in giving credit scores

- There is lack of a substantial framework to regulate collateral registry and legal enforcement

- Majority of the SMEs do not have properly audited financial records

- Most SMEs are owned by sole proprietors and distinguishing the business assets from private assets in challenging

A second challenge thwarting the success of SMEs in Saudi Arabia is the bureaucratic nature of the legal and regulatory frameworks. Approximately 90% of SMEs entrepreneurs are worried about the rigorous bureaucratic procedures (International Finance Corporation 8-50).

It is, therefore, apparent that the status of SMEs in Saudi still needs an appropriate environment to be as effective as they are required.

The study objective

Helping the SMEs in the manufacturing sector in Saudi Arabia to grow

SMEs in the manufacturing sector are some of the most vital tools that Saudi Arabia can use in diversifying the economy and promoting non oil exports. Therefore, support for the SMEs in the manufacturing sector is worthwhile. Supporting the growth of SMEs will streamline manufacturing activities and reduce the monopoly of large enterprises. Additionally, SMEs are capable of providing complimentary services to the large manufacturing firms.

Helping the growth of SMEs will augment the generation of vital benefits in terms of creation of skilled industrial base.

As seen earlier, SMEs in Saudi Arabia faces many challenges that curtail their optimal success. The Saudi Arabia government has made some positive steps in helping the growth of SMEs, especially with the aim of diversifying the economy away from oil. However, the government should be fully committed to solving the problems faced by SMEs in the manufacturing sector. First, the government should strive to come up with a strong supervisory body that reduces the bureaucracy while enhancing efficacy.

It is commonly known that expatriate workers play the biggest roles in the manufacturing sector. As such, there is an overdependence on foreigners in the manufacturing SMEs. It is highly recommended that the Saudi Arabia should give appropriate care to the “Saudization” processes to enhance effective transitions. Helping the SMEs growth should comprise creating more jobs for qualified Saudis (while promoting education and training among the Saudis) to change the labor market trends of depending on foreigners. Manufacturing SMEs entrepreneurs should be trained on managerial aspects such as accounting and financial planning.

Lastly, the Saudi Arabia government should encourage the growth of SMEs in the manufacturing sector by allocating a substantial percentage of its contracts to SMEs.

Methodology

The methodology for this study is based on three approaches, namely:

- Define two important financial factors that help in increasing the financial performance of SMEs in manufacturing sector worldwide

- The collection of the financial ratios of 20 SMEs in manufacturing sector in Saudi Arabia

- Analysis of the collected financial ratios against benchmarked international ratios

Important financial factors

Financing and working capital

Some researchers have established that financially successful SMEs are most likely to utilize more than a single source of finance to start and run the business. While it is generally acknowledged that most SMEs normally use a single source of finance to launch the business, it is observed that SMEs with relatively large number of workers use various sources of finance, including bank loans, remortgaging of personal property, venture capitalists, leasing, and invoice discounting (Kingston Smith LLP and University of Surrey 15). It is also noted that such SMEs are most likely to reinvest profits and focus on inventory management to improve profitability (García‐Teruel and Martínez‐Solano 164).

Cash flow and liquidity management

Most successful SMEs globally proactively manage their cash flow and liquidity. In fact, Shyam B. Bhandari and Rajesh Iyer used cash flow statement based measures to predict failures of SMEs (667-676). In this case, critical success factors or predicting variables such as operating cash flow, operating cash flow margin, cash flow coverage of interest, quick ratio, earning quality, related fiscal years of growth and operations. Besides cash flow, successful SMEs also focus on a wide range of financial success factors, such as sales, marketing, planning, and people management (Kingston Smith LLP and University of Surrey 17). In fact, such SMEs excel in most aspects of their operations.

Ratio Collection

It was determined that 20 SMEs in manufacturing sector in Saudi Arabia would provide sufficient data on financial ratios to explore Financial success factors for SMEs in the Manufacturing Sector in Saudi Arabia. These ratios covered working capital and cash flow ratios. Specifically, working capital ratios were Current Asset Ratio; Current Liability Ratio; Current Ratio; Payable Days; Inventory Days; and Working Capital Days.

On the other hand, cash flow ratios included Operating Cash Flow/Current Liability (OCF/CL); Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR); Operating Cash Flow Return on Total Asset (OCF/Asset); and Cash Flow / Total debts.

Ratio Analysis

The collected data on important financial parameters were analyzed to determine financial ratios that were against benchmarked international ratios to show how Saudi Arabia SMEs were doing financially.

Literature Review

This section covers the importance of financial measurement for SMEs to increase the performance; an overlook at SMEs in in the manufacturing sector worldwide; an overview of performance of SMEs in the manufacturing sector worldwide; and current literature on SMEs in the manufacturing sector.

Importance of financial measurement for SMEs to increase the performance

Many countries, including developed ones such as the UK and Germany, and emerging economies such as Malaysia and South Africa among others understand the relevance of SMEs in job creation and overall contribution to the GDP (Kingston Smith LLP and University of Surrey 1; Jamil and Mohamed 200). As such, care has been taken understand the importance of financial measurement for SMEs as a success factor. In fact, previous studies have shown that SMEs that were focused on financial measurement were more successful and avoided failure while leveraging various sources of finance (Kingston Smith LLP and University of Surrey 5; Bhandari and Iyer 667).

Today, most SMEs have adopted performance measurement systems (PMSs) that play critical roles in supporting managerial development in these companies (Garengo, Biazzo and Bititci 25). These tools assist in performance measurement, analysis, and improvement on performance through better decision-making. In some instances, however, SMEs specifically in the manufacturing sector do not use PMSs due to financial constraints and lack of human resources – factors that significantly contributed to their failure rates (Garengo, Biazzo and Bititci 25).

Nevertheless, specific trends in financial performance measurement have been noted. For instance, as cited in Jamil and Mohamed (200) Tatichi et al. observed that most SMEs were using financial measurement tools such as ROCE, ROI, and ROE. These were the same measurement tools used by large firms. Additionally, financial ratios were largely used by many manufacturing SMEs to assess their financial performances (Bhandari and Iyer 667). Nevertheless, their usage was limited in some SMEs. While other tools such as bankruptcy prediction models are available, it is observed that SMEs rarely use such tools to assess their financial health. It is therefore vital for SMEs to use financial ratios because they have been proven effective as financial measures, and in this case, six ratios have been identified as extremely useful. These tools however require knowledgeable staff. Recent trend have also indicated that SMEs are now focusing on other aspects of operations beyond financial measurements to determine their success.

Overlook at SMEs in manufacturing sector worldwide

Globally, SMEs have influenced the world economy is a significant manner, and they contribute largely to income, employment, and output of products and services. Much attention given to SMEs globally reflects their roles in driving the GDP, job creation, and income generation. Available evidence shows that SMEs are critically relevant for economic growth, in both developed and emerging economies, globally (Edinburgh Group 2). In fact, SMEs, by their tyranny of number, dominate most aspects of the global business. Although the exact, current data on SMEs specifically by sector are difficult to get, available evidence depicts that over 95 percent of businesses across the world are SMEs, responsible for 60 percent of employment in the private sector (Edinburgh Group 12).

Specifically, it was observed that SMEs were responsible for about six percent of the India’s GDP in 2006/7. Despite this, SMEs in the manufacturing sector were responsible for about 40 percent of all industrial product and additional 40 percent of all exports (Edinburgh Group 8). HSBC Bank Canada recently established that most Canadian MMEs were mainly in the wholesale and retail sector (27.2%) while the manufacturing sector consisted of 19.2%. To put into a clear perspective, manufacturing MMEs were the second largest contributors to the national GDP – equivalent to about US$31.3 BILLION (HSBC Bank Canada 1-3).

Germany has observed that some of its SMEs now have a global or regional outlook. In fact, SMEs in the manufacturing sector and others extensively focused on R&D were generally active outside the country.

Worldwide, HSBC evaluated publicly available information about SMEs in different countries and concluded that these firms provided substantial inputs in the global economy in terms of direct employment and contribution to the GDP. While significant differences were observed across countries, HSBC concluded that small enterprises were largely responsible for about 20% to 40% of GDP globally.

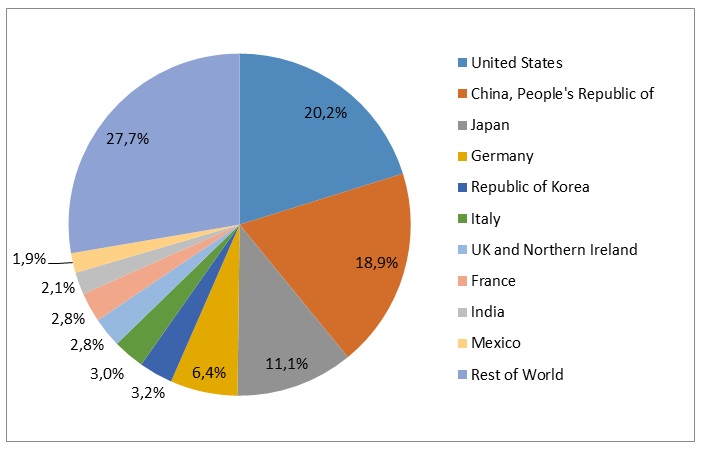

Overlook at performance of SMEs in the Manufacturing Sector worldwide

Globally, manufacturing is regarded as a means of producing wealth or creating wealth in any economy. Conversely, the service sector is considered as wealth consuming (Um Jwali Market Research 15). Data obtained from the United Nations (UN) in 2010 showed that the US was still the largest manufacturing country globally. It accounted for about 20.2% of the global manufacturing. China was ranked the second with 18.9% while Japan was rated as the third largest manufacturer with 11.1%. Germany took the fourth place with 6.4%. It was observed that top ten manufacturing countries in the world accounted for 72.3% of the total manufactured products.

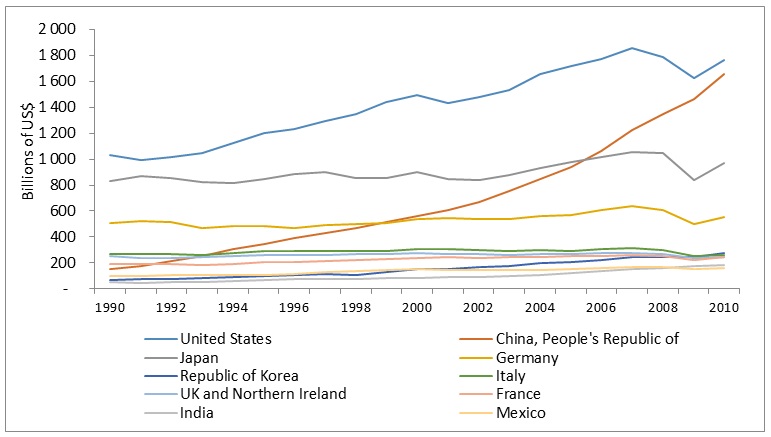

From figure 2, the manufacturing capacities of the ten countries are shown. It is evident that China has increased its manufacturing capacity from $153.2 billion in 1990s to $1.6 trillion in the year 2010. This increment reflects a growth of 3% of the aggregate global manufacturing output since 1990 to 2010 shown as 18.9%. On the other hand, the US manufacturing sector has stayed the same for the last two decades changing from 20.3% in 1990 to 20.2% in 2010. However, the dollar output has increased significantly from $1 trillion to $1.7 trillion (Um Jwali Market Research 15-17).

It is imperative to note that Saudi Arabia, which is the major focus of this research, is not listed among these countries captured in the study. Thus, it is difficult to gauge it against the world ranking manufacturing capacities.

Studies done about SMEs in manufacturing sector

The SME sector is a widely researched field. Both professionals and academics have taken keen interests in SMEs to understand factors that influence their success and failure. Current studies have majorly focused on SMEs after the global financial crisis (Zhao 69). Germany SMEs were able to perform fairly well after the recession. Charles W. Wessner, for instance, touts the success of Germany manufacturing SMEs (Wessner 1). These SMEs are able to manufacture superior products for the niche markets. Besides, they receive considerable support from Fraunhofer Society (Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft). They can then scale up their operations, improve processes and create competitive edge against competition.

Emerging research also focuses on export-oriented SMEs, specifically Chinese SMEs. It is observed that export-oriented SMEs have taken advantage of globalization to export their products regionally and globally. The major markets for China SMEs, for instance, are mainly the US, Japan, Europe, and other emerging economies in Africa (Zhao 70). As such, these SMEs have been touted for their roles in the global economy. At the same time, export-oriented SMEs have been urged to upgrade their low levels of technologies and upgrade other practices to allow them become competitive in the global markets. On the same note, SMEs are encouraged to push for favorable domestic policies to eliminate myriads of challenges they face. These processes would ensure that export-oriented SMEs attain the best structures to deliver sound and rapid economic achievements. In Saudi Arabia, Al-Rashidi also focused on major motivating factors for the Kingdom’s manufacturing SMEs to export their products. The author identified critical factors, including both internal and external ones that influenced SMEs to export their products. The author showed that Saudi export-oriented SMEs were mainly driven by external factors, including availability of market and overall financial returns (Zhao 72).

Financial Success Factors for SMEs in Manufacturing Sector

While multiple factors are responsible for financial success of manufacturing SMEs, specific financial success factors such as working capital and cash flow have been cited as extremely critical for success.

Working capital

Working capital demonstrates how a company is financially healthy and efficient on a short-term basis. Current assets less current liabilities capture working capital of a firm while the ratio (current assets/current liability) shows whether an entity has adequate short-term assets to cover short-term debts. Any ratio below one shows negative working capital and therefore not desirable. A good ratio is above one. Current assets should be more than current liabilities to pay creditors and avoid bankruptcy. A declining working capital over long period requires further investigation, particularly by focusing on sales volumes and account receivables. It shows operational efficiency of a company.

Current Asset Ratio / Current Ratio/ Current Liability Ratio

The above-mentioned ratios refer to a similar issue.

The current ratio is also known as the liquidity ratio, which is used to assess a firm’s abilities to cover its short-term and long-term debts. This ratio is derived from comparing the total current assets against total liabilities.

This ratio considers all assets and liabilities of a firm. Thus, users of financial statements can use this ratio to determine if a firm has abilities to repay accounts payable and other debts using its assets, including cash, inventory, and accounts receivable among others. As such, one can learn a firm’s financial health from this ratio. Higher ratio above one is more preferable because it shows that a firm can meet its obligations. Such a ratio reflects a larger fraction of assets compared to liabilities. While relatively higher ratio is preferred (2), a ratio above three shows that the firm may not be at a good financial state. That is, a firm is poorly utilizing its assets to generate returns, lacks effective mechanisms for securing financing, or does not manage working capital efficiently.

Conversely, current liability ratio (Total Current Liabilities to Total Liabilities) shows how leveraged a firm is. That is, how much money it borrows to fund operations. In this case, low percentage is preferred to show that a firm is less dependent on leverage (borrowed cash). Higher ratio reflects high risk.

Days Working Capital

It refers to the average number of day a company takes to change its working capital into sales revenues, and it is noted that firms with fewer days are more efficient in utilizing their working capital.

It is imperative to consider historical trends of the ratio to understand how a firm has changed over time. Moreover, industry peer comparison would reveal significant insights.

Cash Flow

Cash flow reflects the amount of cash and cash equivalent coming in and going out of an entity, reflecting a company’s operating activities. The difference of cash noted as opening balance and closing balance reflects the cash flow. Some firms have negative cash flow.

A firm can revamp its cash flow through increasing sales, selling some assets, cost cutting, increasing selling price, paying low wages, faster collection, acquiring more equity, or securing a loan facility.

Negative cash flow shows that a firm’s is eroding its current assets. This ratio is useful for determining the quality of a firm’s earning. Specifically, it reflects liquidity and solvent position. Acquiring expensive debts or selling some assets could compromise financial health a company.

Operating Cash Flow/Current Liability (OCF/CL)

The operating cash flow ratio assesses how efficiently the cash flow gained from operating activities has covered current liabilities. The ratio is useful when measuring a firm’s liquidity position on a short-term basis.

A ratio below one shows that a firm cannot meet its current liabilities through operating cash flow. That is, a firm can only meet such obligations by selling its assets, borrowing money, or issuing stock. This situation indicates a lack of self-sufficiency.

Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR)

The DSCR in corporate finance reflects the available cash flow to cover current debt liabilities. The ratio refers to net operating income as a function of several debts required for payment within the fiscal year. It includes all interests, lease, or any other obligations.

A negative cash flow of less than one presents a bad financial health. For instance, the DSCR of.95 shows that a company only has a net operating income to cover 95% of its yearly debts. In other words, such a firm requires external funding to service its short-term debts. Lenders do not like such negative cash flow without supporting external sources of funds.

Operating Cash Flow Return on Total Asset (OCF/Asset)

The ratio shows how well a firm is creating cash from its investments of assets. Higher ratio is preferred, particularly when evaluating manufacturing firms with massive investments in assets. In fact, firms with massive investments in assets should maximize their returns from investments. Low ratio shows that a company is not generating sufficient cash, a situation that is most likely to lead to bankruptcy or cash crunch.

Cash Flow / Total debts

This ratio offers an indication of a firm’s position to cover short-term total debts using annual cash flow from operating activities. Higher percentage ratio is regarded as excellent with improved abilities to cover up debts. In fact, double-digit percentage ratio (between 10 and 99) is preferred because it reflects a favorable financial strength of the company. Low negative percentage ratio may reflect poor cash flow creation or excessive debts.

It is imperative for a company to evaluate any factors responsible for a low ratio by reviewing historical trends of cash flow to debt ratio to detect anomalies in the trends.

Discussion and Analysis

Data were gathered from 20 local SMEs in the Saudi manufacturing sector. All these organizations were mainly from steel and paper segments. The analysis is based on benchmarking the obtained working capital and cash flow ratios against international ratios.

Working Capital

The Current Asset Ratio for Saudi manufacturing SMEs ranges from 26% to 94% with an average percentage of 65% for all the 20 SMEs. In corporate finance, higher ratio (1 or 2 shows that all current liabilities are sufficiently covered by current assets) is preferred (Jackson 1). When the ratio increases, it shows a growing capability to cover debts. In this instance, any ratio below 2 (200%) could unacceptable because in the case of Company 6, for instance, it only has enough current assets to cover 26 percent of the current liabilities. Therefore, given the current context, all the 20 SMEs surveyed have current assets that cannot fully pay off their current liabilities.

Current Liability Ratio should be low to reflect less leverage. There is no specific benchmark ratio because it varies from one industry to another and from one company to another. For Saudi SMEs, the ratio ranged from 40% to 95% with an average of 79%. In fact, only one company had a ratio of 40%. This shows that most Saudi SMEs have borrowed heavily to fund their operations. A ratio of 95% reflects high leverage and therefore high risk.

Current Ratio, just like current asset ratio, should be high (1 or 2 as the international benchmark) (Jackson 1). However, a ratio below one presents inadequate current assets to pay off current debts. The highest observed ratio is 13.44, the lowest ratio is 0.78, and the average is 2.17. About six firms have ratios below one to reflect their inability to pay off their current liabilities.

While there is no specific international benchmark for receivable days, some practices have considered a benchmark of 120 days (Strom 1). Any days above 120 reflect cases of slow-to-pay customers. While the least days are 21 and most days are 337, the average is 128 days – showing that SMEs have poor receivable days in the Kingdom.

Days payable has no specific benchmark, and it is advisable to look at the industry average because of fluctuation (Strom 1). While the least days are 8, there are as high as 212 days with average days payable of 63 days among all the SMEs. Hence, Company 4 with 8 days payable should consider increasing the days to improve cash flow. Longer days could reflect poor performance of the company, and the performance may eventually hurt the relationship with suppliers.

Inventory days should be as few as possible to reflect efficiency of the company. It varies from industry to industry and company to company. For Saudi SMEs, the least days observed are 90 with high of 277 and an average of 178 days.

Working capital days should be preferably few. However, Saudi SMEs have an average of 263 days, a low of 145 days with highest days of 417. An internal analysis to determine trends for a company is important rather an international benchmark.

Cash Flow

Operating Cash Flow/Current Liability (OCF/CL) is preferred with relatively higher ratio. The status of most Saudi SMEs analyzed shows relatively low ratios with a maximum of 43% and a low of -6%. In fact, about three companies have lost their liquidity position while more than five firms are most likely to look for alternative funds to service debts.

Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) is generally poor among Saudi SMEs. In fact, only two companies (9 and 11) have sufficient net operating income to pay off their annual debts. Other companies require external sources of financing to meet their obligations

Operating Cash Flow Return on Total Asset (OCF/Asset) ratio shows that most of these SMEs have relatively low ratios that could reflect possible cash crunch and bankruptcy. As such, these firms should maximize returns from their massive investments in assets.

Cash Flow / Total debts should reflect the preferred benchmark of double-digit percentage. More than ten firms currently meet this requirement and therefore positive financial strength. Conversely, other firms with relatively low ratios have cash flow problems and relatively high debts.

Conclusion

Manufacturing SMEs continue to play critical economic roles in both developed and emerging economies. The research paper has focused on financial success factors for SMEs in the manufacturing sector in Saudi Arabia. It shows that financial ratio analysis used across industries globally could assist many SMEs to determine their financial health and success. As such, SMEs should adopt such performance measure tools with the aim of improving decision-making.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the Professor for his guidance and support during this research. We also thank SMEs experts and bankers who provided vital insights on manufacturing SMEs in Saudi Arabia.

Works Cited

Alia, Youcef Ali. “The Effectiveness of Small and Medium Enterprises Adoption as a Strategic Option to Solve Unemployment Problem in the Arab World, an Example of Algeria.” International Journal of Business and Social Science 5.4 (2014): 160-171. Print.

Al-Rashidi, Yousif Abdullah. “Exporting Motivations and Saudi SMEs: An Exploratory Study.” Proceedings of 8th Asian Business Research Conference. Bangkok, Thailand: Yousif Abdullah, 2013. 1-20. Print.

Bhandari, Shyam B. and Rajesh Iyer. “Predicting Business Failure Using Cash Flow Statement Based Measures.” Managerial Finance 39.7 (2013): 667-676. Print.

Chamber, Jeddah. Small Medium Enterprises in Saudi Arabia Report. 2015. Print.

Edinburgh Group. Growing the Global Economy through SMEs. n.d. Web.

European Commission. Growth: Internal market, Industry, Entrepreneurship, and SMEs. 2016. Web.

García‐Teruel, Pedro Juan and Pedro Martínez‐Solano. “Effects of Working Capital Management on SME Profitability.” International Journal of Managerial Finance 3.2 (2007): 164 – 177. Print.

Garengo, Patrizia, Stefano Biazzo and Umit S. Bititci. “Performance Measurement Systems in SMEs: A Review for a Research Agenda.” International Journal of Management Reviews 7.1 (2005): 25– 47. Print.

Holátová, Darja and Monika Březinová. “Basic Characteristics of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Terms of Their Goals.” International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4.15 (2013): 99-103. Print.

HSBC Bank Canada. Canada’s Unsung Corporate Heroes: Mid-market Enterprises are the Overlooked Engine of Our National Economy. Canada: HSBC, 2015. Print.

International Finance Corporation. Islamic Banking Opportunities Across Small and Medium Enterprises in MENA. 2014. Web.

Jackson, Amy. United States: Ratio Analysis And Industry Benchmarking Reveal Hidden Messages In Your Financial Statements. 2014. Web

Jamil, CheZuriana Muhammad and Rapiah Mohamed. “Performance Measurement System (PMS) in Small Medium Enterprises (SMES): A Practical Modified Framework.” World Journal of Social Sciences 1.3 (2011): 200-212. Print.

Katua, Ngui Thomas. “The Role of SMEs in Employment Creation and Economic Growth in Selected Countries.” International Journal of Education and Research, 2.12 (2014): 461-472. Print.

Kingston Smith LLP and University of Surrey. Success in Challenging Times: Key Lessons for UK SMEs. 2012. Web.

Kongolo, Mukole. “Job Creation versus Job Shedding and the Role of SMEs in Economic Development.” African Journal of Business Management, 4.11 (2010): 2288-2295. Print.

Kushnir, Khrystyna. How Do Economies Define Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs)? 2010. Web.

Strom, Stephanie. “Big Companies Pay Later, Squeezing Their Suppliers.” The New York Times. 2015. Web.

The World Bank Group. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Finance . 2015. Web.

Um Jwali Market Research. Research on the Performance of the Manufacturing Sector. South Africa: Um Jwali Market Research, 2012. Print.

Wessner, Charles W. How Does Germany Do It? 2013. Web.

Zhao, Yanan. “Research on the Approaches of the Participation of China’s SMEs in International Trade under Financial Crisis.” International Journal of Business and Management 5.1 (2010): 69-73. Print.